Justice Department Sought Reporter Records from Security Firm Proofpoint, in Bid to Unmask Leak Sources

Documents unsealed by a court this week reveal that the Justice Department didn't just go after email providers to obtain reporter records, but also went after the security firm Proofpoint

News that the Trump administration’s Justice Department secretly sought the phone and email records of reporters to uncover the identity of their sources caused a stir in recent months when the Justice Department began disclosing the information to targeted journalists and publications under the Biden administration.

But a new revelation this week raises even more questions about the lengths the department was willing to go to obtain reporter records and identify sources.

On Tuesday evening the Washington Post reported that last year the Justice Department sought the email records of several of its reporters by sending a court order to a third-party security firm — Proofpoint — that appears to be engaged in filtering the media outlet's email for malicious threats.

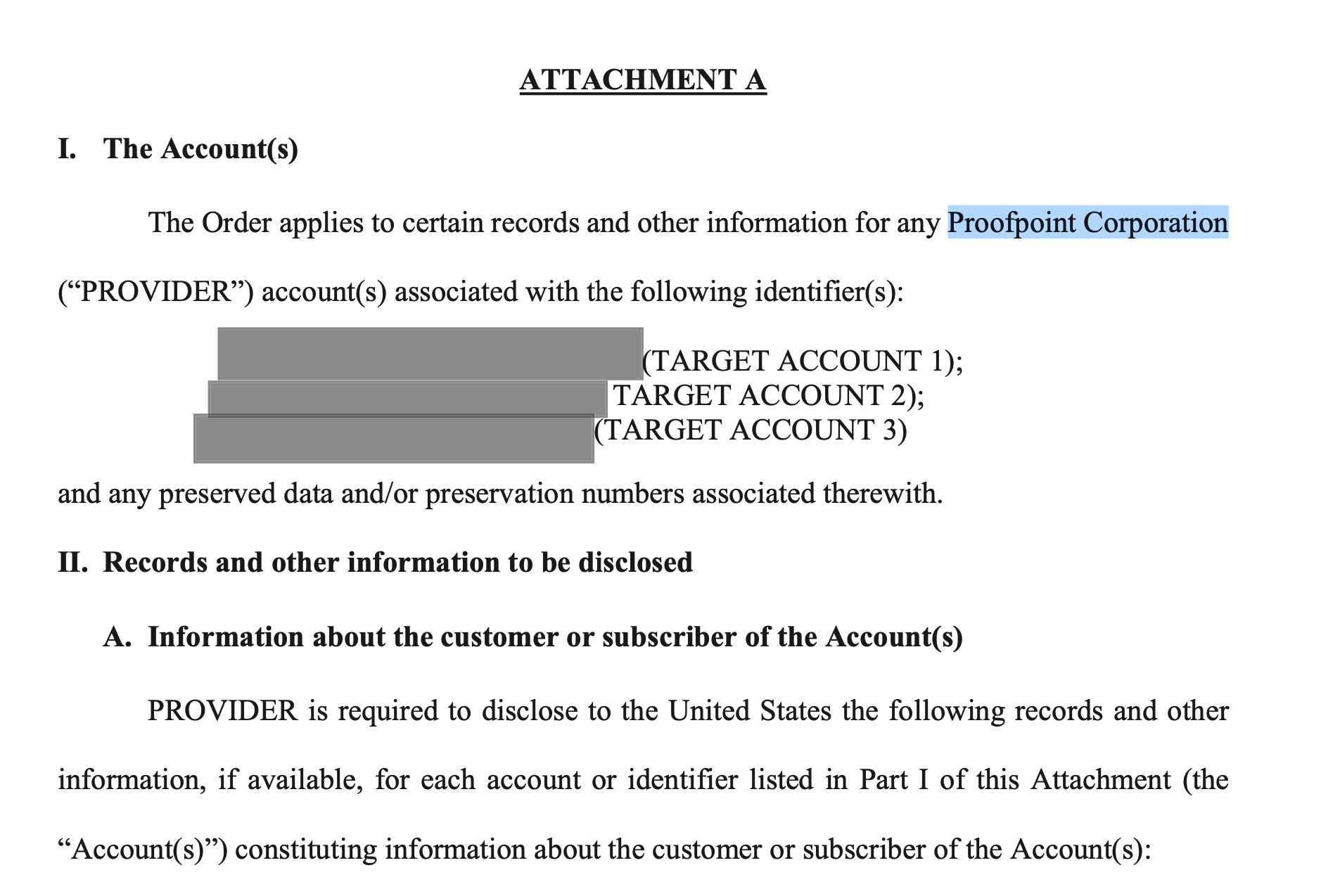

The DoJ’s 12-page application for the court order, which the Post published, is redacted and does not mention Proofpoint by name as the company that was targeted in the court order. That application describes the company only as “an electronic communication service and/or remote computing service provider.” But another document filed with the DC District Court was poorly redacted and does name Proofpoint as the provider that received the court order.

The request for email records were only for non-content information — essentially the email metadata, which shows any email addresses that sent to or received communication from a targeted email address (in this case the work and personal email addresses of the Washington Post journalists).

Typically Justice Department requests involve a court order sent to a telecom or email service provider — such as AT&T, Microsoft or Google — all companies that directly provide communication service. Proofpoint, however, is an information security company whose servers simply filter email communication sent to a customer’s domain, in order to uncover phishing attempts or malicious attachments and links among those emails.

According to the Post story, the Justice Department didn’t ultimately receive the requested information. But going after a third-party security firm that is not the provider of a communication service is a concerning move says Kurt Opsahl, deputy executive director and general counsel for the Electronic Frontier Foundation. It signals that the Justice Department is willing — or at least was willing under the Trump administration — to seek information from any company that touches a target’s communications, regardless of how tangential their role in that communication is.

“It suggests that the government is going to look over the entire chain of people who touched the data to try to find the point to send a subpoena,” Opsahl said.

Bypassing Barriers?

Opsahl believes the Justice Department may have gone after Proofpoint for the data in order to sidestep barriers that companies like Microsoft and Google have erected in recent years to protect customer data from government requests. Both companies have published policies indicating that they push back when requests for customer data are inappropriate or too broad and that they also seek, when appropriate, to notify customers when the government has sought their communication. They also, in the case of enterprise customers who use their email or cloud services, urge law enforcement to go directly to those customers to seek the information when practical, before approaching the third-party providers to obtain it.

“The policies of the large providers are known and published by them and are often included in their law enforcement response guidelines,” said Opsahl, “so the government would be already aware of the promises these companies have given [customers] to provide notice” when law enforcement agencies seek their records.

Proofpoint, however, doesn’t have a published policy about how it handles law enforcement requests like this, and may not have received such a request before. This may be why the government sent the request to them, Opsahl noted.

He says it’s a warning to customers that even if their provider has strong protections against improper law enforcement requests, the government “can bypass that by going to a service provider that layers on top of that provider” and noted that it’s particularly “sad and ironic” that the government targeted a security firm in this case — “a company that would be brought into protect the mail for threats, actually becomes an attack vector.”

The Justice Department didn’t respond to an inquiry about the matter.

But Daniel Kahn Gillmor, senior staff technologist for the ACLU's Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project, said the Justice Department may have approached Proofpoint for a different reason — because it didn’t know who else to approach. It’s possible that the Washington Post hosts its own email servers, and the Justice Department didn’t want to ask the paper directly for its reporters’ records. Or it’s possible the Justice Department was unable to determine who controls the publication’s email servers — the Post or a third-party email provider — but was able to determine who was filtering that email.

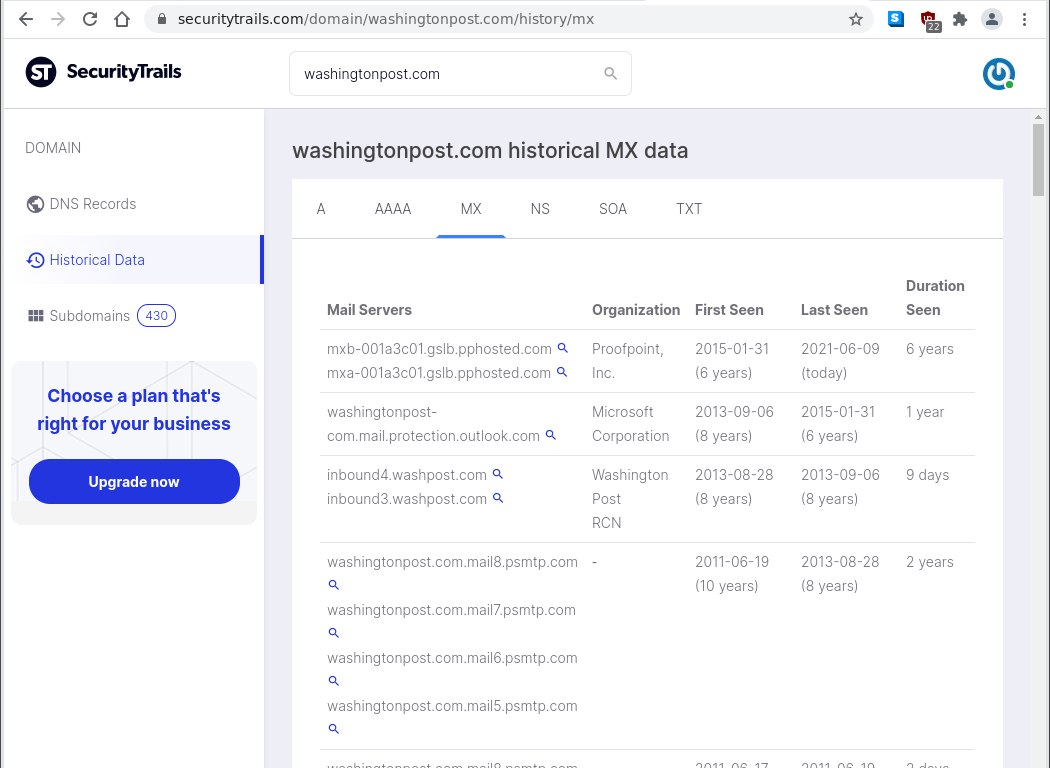

Public DNS records often show information about who is providing email filtering services for an organization, and in this case they do show that Proofpoint is providing this service for the Washington Post.

DNS records show the path of email sent to an organization’s domain. If email filtering is supplied by a third-party company before it reaches the organization, that company’s domain will often be identified in the DNS records as a hop the email passes through on its way to the recipient. The DNS records for the Washington Post show that email sent to the company goes first to a Proofpoint server — identified by the domain name pphosted.com in the DNS records. Beyond that point, the records don’t show where the email goes, which could be a third-party email provider like Microsoft or Google, or it could just go directly to the Washington Post if it hosts its own email servers. Proofpoint’s own internal logs would show where the email goes after it passes through that company’s filters.

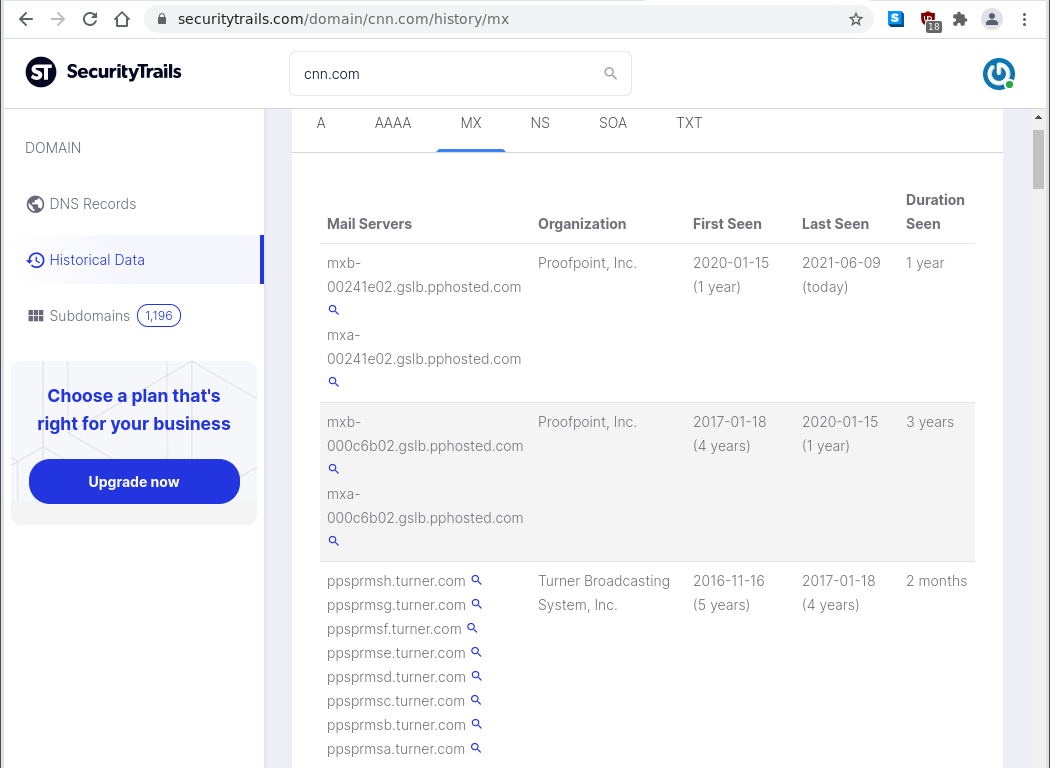

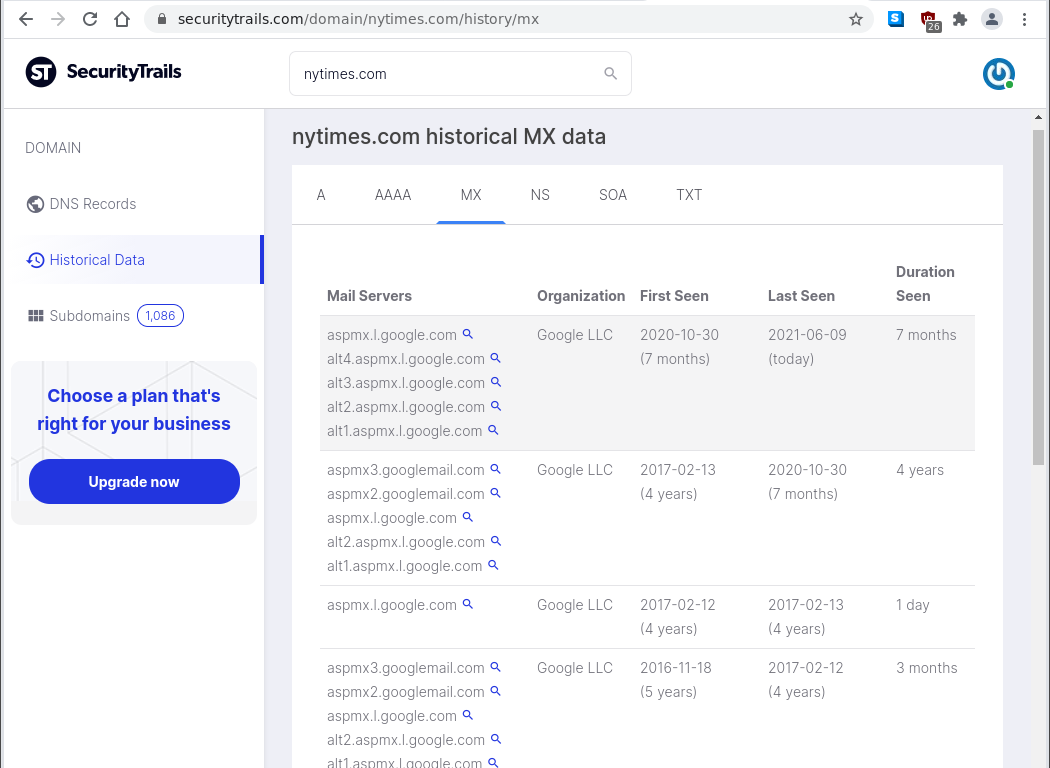

DNS records show that Proofpoint has been providing email filtering services for the Washington Post since January 2015 and for CNN since January 2017. But Google has been providing email filtering for the New York Times since September 2013.

Regardless of whether the Justice Department sent the order to Proofpoint to bypass the Washington Post or its email provider, or sent it to Proofpoint because it didn’t know who the Post’s third-party email provider was, Gillmor says the issue raises serious questions for any organization that uses third-party providers.

“When you engage a security company to do filtering on your data, you are giving that security company access to your data, and that makes them a potential target for this kind of inquiry,” he said. “Employing a security company means trusting that company to not leak information they have about your internal communication.”

Proofpoint didn’t initially reply to an inquiry from Zero Day before this story published, but did send answers to questions after. Asked how Proofpoint responded to the court order when the company received it, a spokesman replied in an email:

“[A]s is typical as an email threat detection provider and not an email service provider, we only had and provided the DOJ with the contact information at the Washington Post and the distributor to whom we sold the threat detection services.”

Asked what the company’s general policy is for responding to such requests, he replied: “Proofpoint provides email threat detection services, so we do not have the type of information typically sought by law enforcement…. Once we explain this to the requesting agency, that typically ends their inquiry. However, if the requestor persists, and the subpoena or warrant is not accompanied by a non-disclosure order (NDO) Proofpoint informs and works with our customer on the appropriate response. In other cases, we engage counsel to determine the appropriate action, which may include disclosing non-sensitive, basic customer information (such as customer company name and dates of service), and notifying our customer.”

Unmasking Sources

Since President Joe Biden took office in January the Justice Department has notified a number of media outlets about activity under the previous administration to obtain reporter records through secret court orders. The aim of these orders was to uncover the identify of sources who leaked information to reporters that revealed classified information or information that was embarrassing to the Trump administration. This included, for example, conversations that had occurred between officials for the Trump campaign and Russian ambassador Sergey Kislyak to set up private communication channels before Trump took office. The Justice Department suspected that someone in Congress was the source of the leak and hoped to unmask their identity before Trump left office earlier this year.

Media organizations have criticized the leak investigations as “profoundly” undermining press freedom and having a chilling effect on the press’s ability to provide oversight of government. They also say the practice is a violation of standing Justice Department policies whereby officials have promised to first provide media organizations with prior notice of their intent to seek the records of reporters (unless such notice could jeopardize an investigation or national security). Under that same policy, Justice Department officials have to obtain approval directly from the attorney general before seeking the records of journalists.

Biden has said he would not allow his Justice Department to seek reporter records, calling it “simply wrong.” And in the last few months at least four media outlets have received notification that the previous administration had sought the records of their reporters. The DC District Court has also begun to unseal documents in the leak investigations, which is how Proofpoint’s role in the matter was revealed.

The Washington Post reported in May that federal prosecutors under the Trump administration last year had sought three-year-old phone and email records for several of its reporters. A New York Times story published in June described a similar effort by the Justice Department to obtain the phone records and email records of four Times journalists for a three-month period in 2017.

In each case, the target of the Justice Department investigations were not the reporters themselves but anonymous sources who provided them with information for stories.

The Justice Department filed applications to obtain court orders for the communication records on December 22 last year, the day before Attorney General William Barr left his position (he had announced his resignation from the AG job earlier that month). This indicates the effort was a last-ditch aggressive effort by the Trump administration to uncover the identity of sources who had leaked information three years earlier.

The DC District Court didn’t approve the applications for the court orders until January 5, 2021, not long before Trump left office. In both cases involving the Washington Post and New York Times reporters, the Justice Department did obtain the toll records or call logs for the reporters — records that list the calls made to and from a targeted phone (such as the phone numbers involved and the date and time of the calls). But they did not obtain the email metadata that they had requested. According to the Times, the court order for the email records of their reporters went to Google. Google didn't initially respond to the order but then told prosecutors in February that it would not provide the information unless it could first tell the New York Times about the request. The Justice Department agreed, under the condition that the Times would be prohibited from disclosing that information to sources or anyone else. But then the Justice Department closed the leak investigations and dropped the requests for reporter records.

In the case of the Washington Post reporters, it’s not clear if Proofpoint ever responded to the court order at all or how it responded if it did.

Opsahl and Gillmor say it will be interesting to see what else will be revealed in the coming days, as media organizations continue to push the Justice Department and the court to unseal more documents in the leak investigation. The Justice Department inspector general is also conducting an investigation into Trump-era leak investigations and the hunt for journalist records and sources, which may reveal more information about the department’s tactics under Trump.

Update 5:00 pm PT: With comments from Proofpoint.

If you found this article useful or interesting, feel free to share it:

If you’d like to receive other articles like this sent directly to your email inbox, subscribe here: